Beyond disabilities: widening the inclusivity scope in Museums and cultural institutions (1/3)

Museums and galleries have increased considerably their politics and actions when it comes to reflect and explore diversity, whether it is shown in their collections or in their public agenda. However, most of the time these approaches relay more in a rhetorical basis than in real praxis.

On the basis of some examples given by different museums, this thread of three different posts will give an overview about three perspectives that cross transversally over the gap of inclusivity in museums aside of physical or intellectual boundaries. The crossroad between three topics very well studied on their own, such as LGBTQIA+ representation, the inclusion of migrant communities, and the participation of older people, should open a debate about how can museums create more inclusive and more representative spaces further than providing them for other activities unrelated with the museum itself (even though this is a great strategy for letting people know the possibilities of institutions such as museums and galleries aside art exhibitions).

But first let’s make clear some aspects about what is expected to be done by museums and why they shouldn’t exactly function as social workers or governmental institutions. Society has been changing a lot during the past decades and it has prompted discussions about institutional violence and neglected topics like violence against LGTBQIA+ community, the refugees’ crises or the problem of isolation and abandonment of a more diverse range of older adults. Initiatives like Museums are not neutral expose this reality and make us more aware about what museums can actually do and what can they become.

It is very easy to fall in this urge to provide help further aside of what museums can actually offer. Then, what can museums actually do about this situation?

Museums should act as agents of social change revising their past actions and mistakes, rethinking about the way their collections have been settled and also giving access to more people not only to enjoy and understand their collections, but also re-reading, enlarging and improving them. Maria Vlachou, founder of various platforms regarding museums, accessibility and diversity, shared in her presentationAre we failing? on the 23rd Annual Conference of the Network of European Museums Organizations her vision about what museums are.

In Vlachou’s words, “museums aren’t islands”. They’re about heritage, identity, and collective memory. They’re about past, present, and future; they are places of knowledge and encounter, dialogue about respect and tolerance, they have an educational role and a social role. The task of collecting isn’t about the object’s sake alone. Museums can produce knowledge with those objects. This knowledge makes us grow as better human beings by becoming more critical and more involved, and above all: becoming more comprehensive (this isn’t about tolerance, it’s about understanding and engaging) by recognizing humanity of others fully.

Museums are facing a big challenge, but a challenge whose nature is not unknown to them: it is the ‘we’ and the ‘others’; identity and inclusion; barbarism and culture; it is precisely what museums are (or should be) about.(Vlachou, 2005).

These words are addressed to the reality of migration and how it is reflected in museums, but they can be perfectly applied to other realities such as the LGBTQIA+ community or the invisible majority of older adults, that also intersect in these two categories of migrants and LGBTQIA+ people. Museums theoretically recognize these communities as a ‘we’ and not as ‘others’. However, this has been little reflected on museums’ collections and exhibitions. Representation of their collective memory and their identity aren’t new at all in any museum’s agenda, but they should be addressed from the perspective and participation of people forming these communities and also with help from other institutions and specialists.

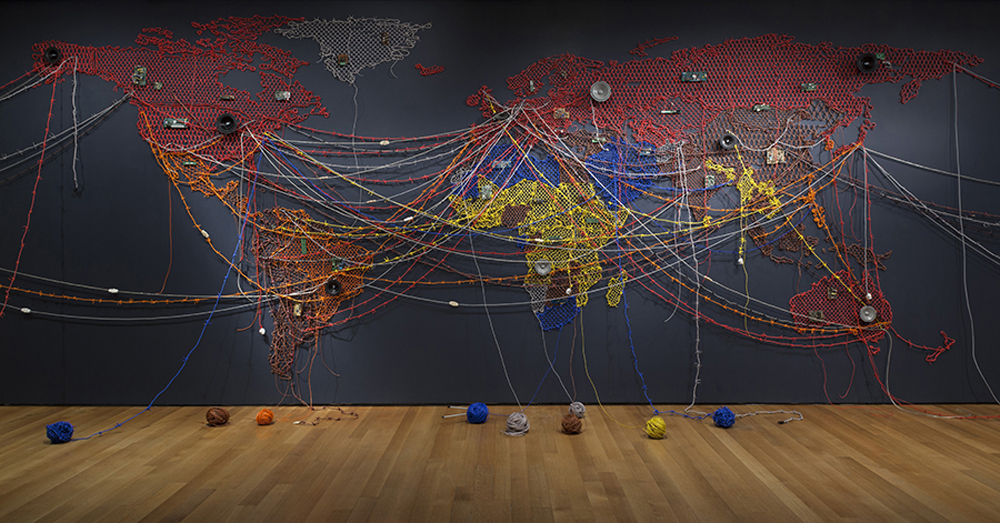

When it comes to migration, it is interesting and important that museums take board of the experiences and the mediation of people from different origins that are already in the country, so the encounter with the ‘new other yet to come' and 'yet to make a home of this new place' could reach further in a cultural and in a social way. This aspect has been approached in very different ways, putting into question the colonial and monopolizing tendency that have been practiced historically.

The capacity of museums to reconsider this historical approach to their collections can give as a result a re-read the objects that they already have, giving them new meanings and also making them more accessible to other people with different cultural backgrounds. This happened with the Världkulturmuseet (World Culture Museum) of Gothenburg, Sweden, in 2005.

The example of the more participative model that the Världkulturmuseet started within the exhibition Horizons: Voices from a Global Africa sets the spotlight on a switch between the proposal of interpreting objects further from the history of their creators and users –and so making history about how were they collected and who collected them- to a more engaging and participative approach. The purpose of the exhibition Horizons: Voices from a Global Africa was to establish a relationship between the museum’s collection and the living and contemporary context of immigration in Sweden. The process of curating the exhibition counted with the participation of immigrant associations of people from the Horn of Africa in order to reinterpret the collections of Ancient Abyssinia displayed in it. These people became –in a way- associate curators and also worked as guides and mediators during visits organized by these institutions, thus reaching a wider public and laying foundations for a more welcoming and engaging space towards the museum itself. This philosophy was to be continued in future exhibitions and so it could be found in ongoing educational projects like Afrika pågår(Ongoing Africa).

The encounter with the ‘other yet to come’ was better addressed in a more recent exhibition from 2019 held in the Centro Galego de Arte Contemporánea (Galician Center of Contemporary Art) called We Refugees. Before the opening of the exhibition, the CGAC organized some series of seminars with the aim of a stimulating in-depth approach to the diversity of the refugees’ situation. These seminars also addressed some other objects of the collection, not only those curated by the curators in charge of the exhibition We Refugees. These seminars were open to all kinds of people, presented as a safe space for learning and discussing. The exhibition wanted to communicate from the testimonies of different people exiled in different countries of Europe how was their struggle for getting the right of asylum, conceived as one of the fundamental pillars of modern European democracies and which now is being violated in many borders –the exhibition also addressed other polemics on migration and right of asylum, pointing out the situation in Spanish borders in the African borders of Ceuta and Melilla.

Whereas these two models of engaging people with different origins in more plural and diverse societies are regarded as good practice examples, there are still some clichés to fight. There should be a compromise between research and first-hand stories, there should be also a wake-up call of the social conditions that migrants are bound to in their destination land and how museums and cultural industries can interact in the areas where these people settle in the cities. These people also get old and are permeated with determined gender constructions and ideologies. For this reason it is important to dedicate specific cultural institutions for each of these fronts in social inclusion without forgetting that is all a crossroad. As Gloria Anzaldúa wrote, to break down the dualities that pierce and tear apart society –such as subject-object duality, male-female, colored-white- and keep people as prisoners, we should work together on healing this split. We should be conscious about how these differences have routed deep in our lives, our culture, our languages, and our thoughts.

In this context, museums should ask themselves which stake they could hold in this process, turning into a more inclusive and cohesive reality and agent in society, embracing diversity and making it accessible and recognizable for everyone.

This topic will be expanded next week in another post where issues such as representation, inclusion and participation are approached from an LGTBQIA+ perspective. Examples of other interesting museum projects worldwide will be given, highlighting the meeting points of these crossroads of gender, origins and age and how cultural institutions should take part of these circumstances without hindering their fights for equal rights, visualization and social acceptance.